The Rise of ASME in Washington

The Rise of ASME in Washington

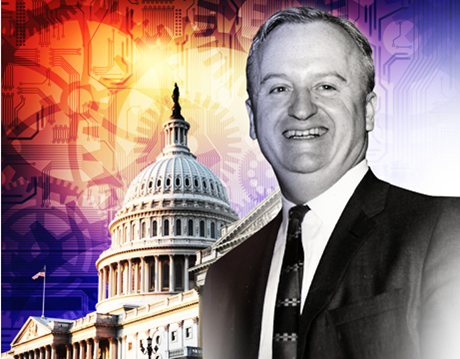

A succession of ASME presidents in the post-World War II period believed the Society should become a forceful voice for engineering, both to advocate for the profession and to offer technical expertise to national decision-makers–and that it needed a presence in Washington, D.C. to do so. Perhaps the pivotal figure in realizing this vision was Donald E. Marlowe, who, during his tenure as Dean of the School of Engineering and Architecture at Washington D.C.’s Catholic University of America, served as ASME’s 88th president in 1969-1970.

During and after the Second World War, Marlowe served in the U.S. Navy as Associate Director of the Naval Ordinance Laboratory, where, as he relates in his oral history interview, he “had a marvelous time” working out the mechanics of underwater weaponry and subjecting submarine armor to increasingly violent depth charge blasts. In the end, Marlowe spent more than two decades living and working at the nation’s center of legislation and governance; it convinced him that Washington was vital to the future of the profession.

“[My] experiences left me with two very strong feelings about technical society activities in Washington,” he says. “One, I was a very strong supporter of a unified engineering society… The other, I was convinced that engineering as a profession and the societies in particular were very poorly represented in the legislature … Those two obsessions really determined the major thrust that I tried to put on the road as I became President of ASME.”

The “Overriding Goal” they formulated, the one that subsumed all the others, was that ASME should “move vigorously from what is now essentially a technical society to a truly professional society sensitive to the engineer’s responsibility to the public, and dedicated to a leadership role in making technology a true servant of man.”

Marlowe believed strongly that a Washington office would be necessary to support the new goals, manifestly including #11: “To provide government at all levels with technical advice in the public interest and to develop a climate of understanding and credibility that will foster a continuing dialogue.”

Dr. Reginald Vachon, now an ASME past president himself as well as a member of more than 55 years’ standing, was a delegate at Arden House as well as a member of the committee which shortly thereafter approved the foundation of the DC Office. “I worked with Don Marlowe for years, back when I was one of the ‘young voices’ in the society,” Vachon says. “Yes, Don was instrumental in establishing the Washington Center. It was controversial. Members were concerned ASME would be accused of lobbying if we established a Washington office. But I am also a lawyer. We brought the law right into the committee meeting and showed the members it wasn’t going to be a problem.”

The committee was persuaded, and in 1972 ASME’s Washington Center was open for business.

Forty-one years later, today’s Washington Center is an important nexus of Society activity. Opened with a staff of two, it’s now home to 18 staffers who work in a range of fields important to today’s ASME: government relations, public affairs and outreach, strategic issues, diversity and inclusion strategy, innovation, and research & technology development among them. ASME’s Washington Center also serves as the offices of the ASME Foundation, the Federal Fellows program, the Industry Advisory Board, and as the center of program development for ASME’s department of Standards and Certification.

Thus from President Don Marlowe’s “obsession” more than forty years ago did a thriving center of ASME’s work come into being. We think that if he were still with us today, President Marlowe would be pleased to see what ASME has made of his vision.

© The copyright of this program is owned by ASME.